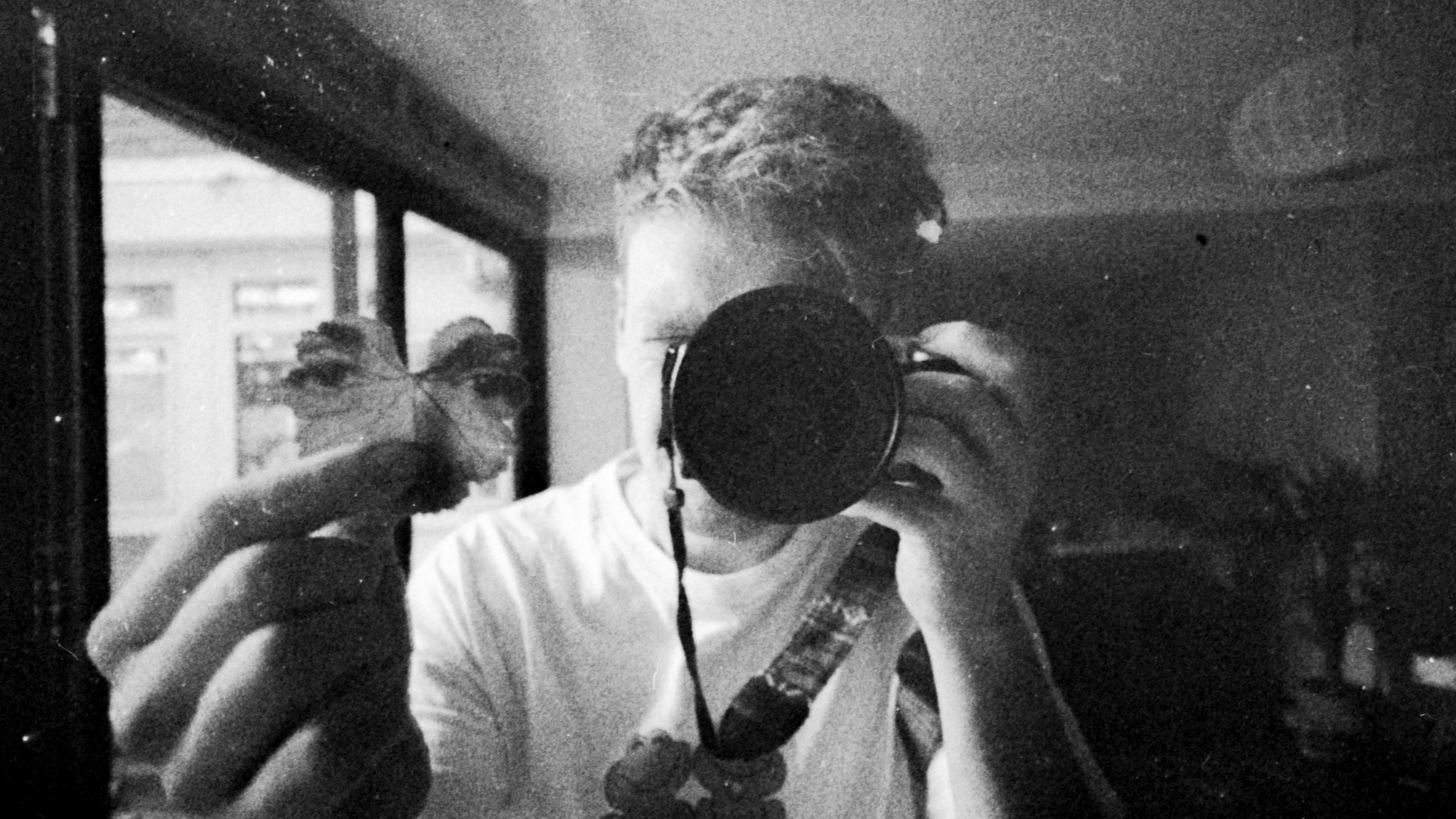

Edd Carr on 'I AM A DARKROOM'

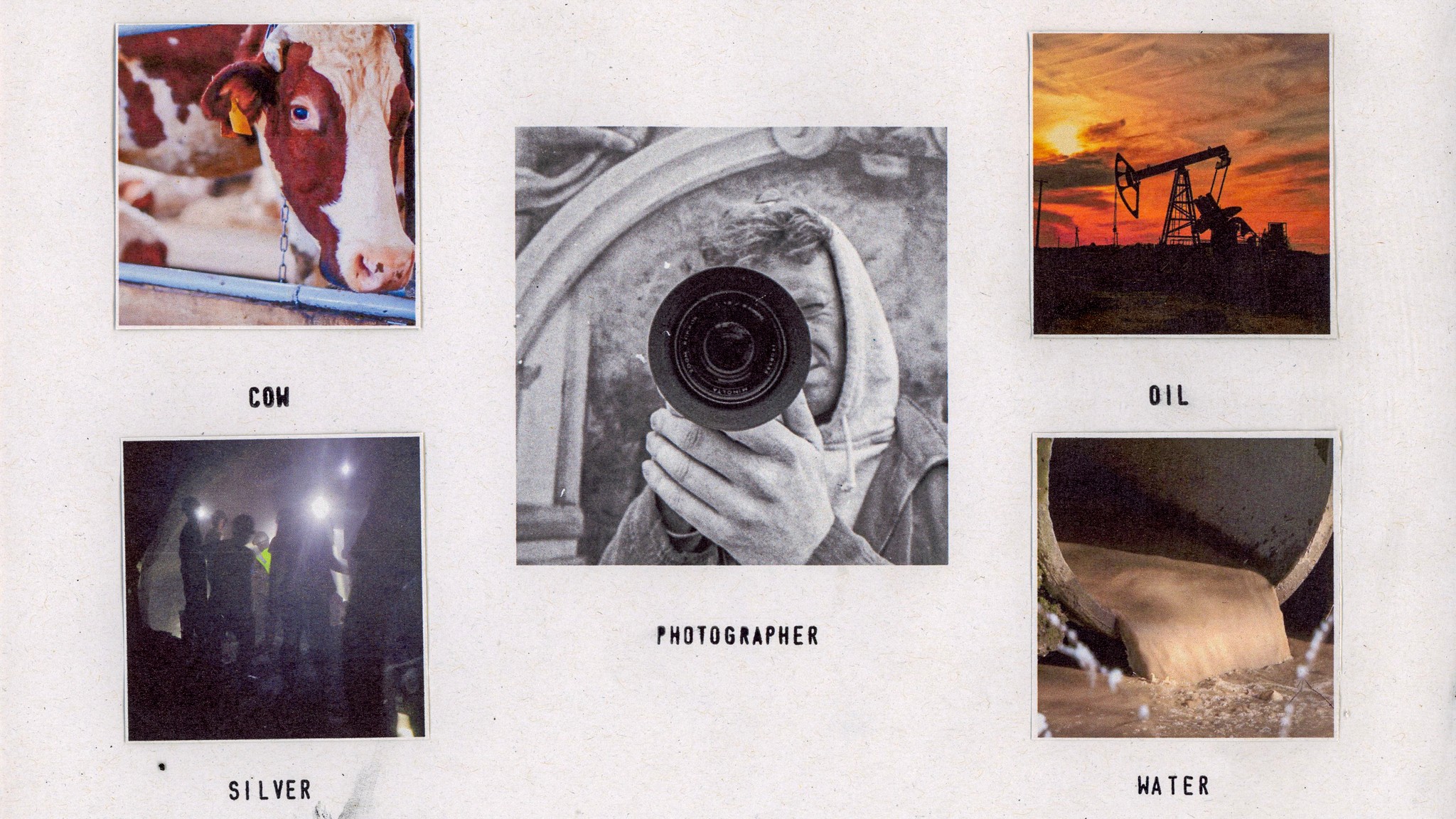

Edd Carr says that for him, it all began with the cows. Like so many of us, Carr had been practising photography without giving too much thought to the material effects of industrial film production. When he discovered that cow gelatin was an irreplaceable ingredient in film, the idea that the crushed and melted bones of living, thinking, feeling beings were in every image he produced made him think about photography as an infinite, wide-reaching set of relations between us and our environment.

Co-founded by Carr, The Sustainable Darkroom is an organisation dedicated to the research, development and advocacy of eco-friendly alternatives to analogue and digital photographic processes. The limitations of analogue become opportunities to collaborate with organic materials, giving up an element of control. Used coffee grounds, lemon rinds and soil all become building blocks for a new way of capturing the world around us.

His moving image works have explored human and non-human worlds, such as the interwoven narratives of insect extinction, the life cycle of a butterfly, and childhood trauma. His methods often incorporate natural elements including rain, leaves, and “sewage soup” - reframing photography as an organism of its own.

In I AM A DARKROOM, a film commissioned by DoBeDo for the Reely and Truly documentary series, Carr explores the theme of the “photographic garden” by interviewing residents of The Sustainable Darkroom and discussing their practises, which range from incorporating foraged seaweed and kelp in film to using slow photography methods to print A.I. portraits of non-existent people. Carr adapts photographic processes to craft these moving images, spliced together to create an intricate visual orchestra, whilst inviting the environment to have a hand in its expression.

Life is messy, and The Sustainable Darkroom and the photographers it fosters are carving out radical new paths in which our relationship to the non-human world, flawed as it is, can be translated into a beautiful and tangible visual language that isn’t necessarily built to last. The result is as poetic as it is necessary in the face of an uncertain ecological future.

What processes were used to create your film I Am A Darkroom?

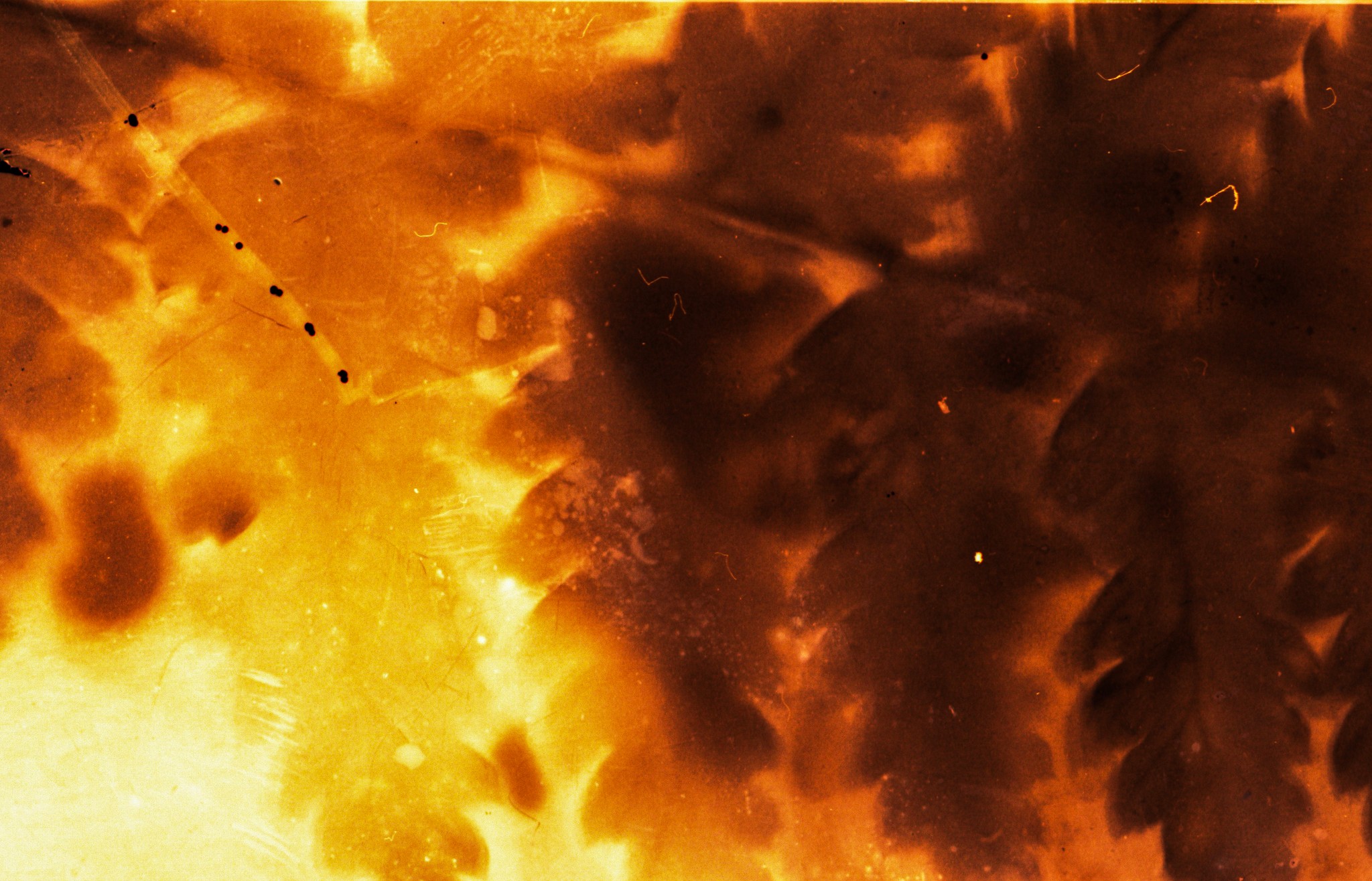

The bulk of the film was shot on Tri-X Super 8, which was then developed in a mixture of coffee and herbs, with the latter grown in our darkroom garden in Leeds. The black and white stills were also developed this way, using film stocks Kentmere 400 and Ilford HP5.

Other than that, there is a pretty long list of processes used, probably the most I’ve ever combined in one single project:

- Phytograms (plants dipped in plant-based chemistry ingredients and applied directly to the photographic surface).

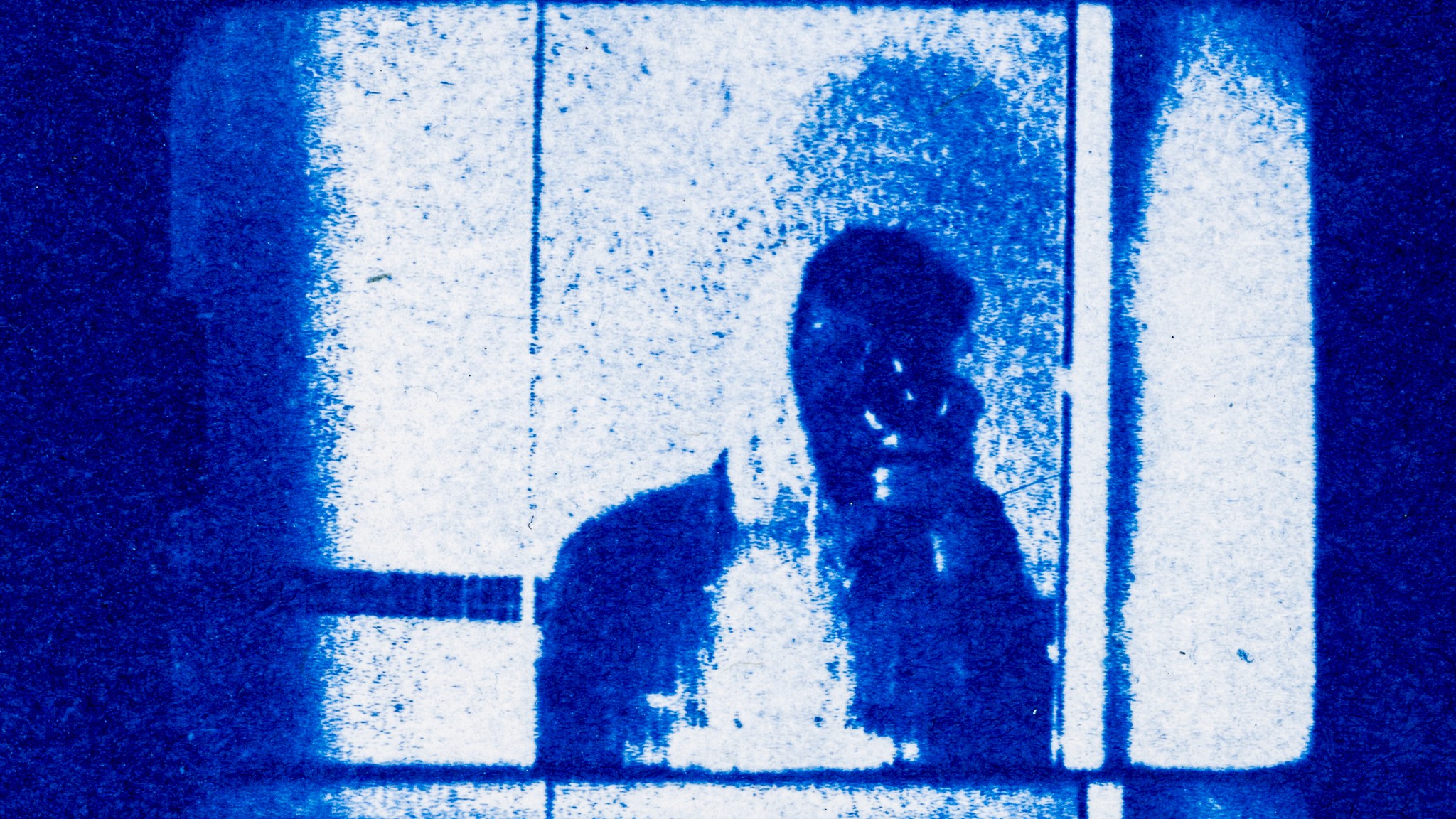

- Cyanotype animation on different surfaces including paper, seashells, waste coffee cups, waste Amazon packaging, red card.

- Soil Chromatography.

- Eco-inkjet on recycled paper, detailed with ink, homemade charcoal, soil.

- Chemigrams.

- 2000s digital camcorder.

- Darkroom paper prints in waste developer.

- Monoprints with watercolour paint.

- Super 8 stills transformed by AI, then printed and sanded.

- Ecoprinting.

- Leaf and bark rubbings.

- Paper collage.

- Oarweed cut into 8mm strips.

- Frames printed on sea kelp.

- Antho-cyanotypes.

- Kodak slide frames with seaweed.

- Anthotype animation.

- Miniature pinhole animation.

- Sewage film soup.

- Scratch film.

- Smartphone footage.

- Hand-printed titles using letterpress.

Can you describe what you like about using these processes in your work?

I first got into photography using a digital camera a few years ago, when I was a dog walker. I would take pictures of dogs, and in my spare time some generic landscapes and sunsets. When I studied photography I became frustrated with the digital process - I was so focused on the image on the little screen instead of being engaged with the physical world around me that I decided to start using more hands-on processes. I started to think about how I could animate with a lot of these processes (e.g. cyanotype) and that began the development of my current practice.

Were any of these new to you?

In terms of Super 8, this is the first time I’ve used it for a project, so please excuse the many imperfections. Fundamentally, it was about getting my hands dirty and physically engaging with the work on a material level, and not feeling so detached. The sustainable stuff naturally came later as questions around the safety and ecological impact of these processes began to arise. I’m sure one day A.I. will be able to replicate the aesthetic of analogue to a tee, but for me I prefer the physicality, which hopefully comes through in the film’s many textures.

What processes used in traditional analogue photography are detrimental to the environment?

Big question! But I guess if we are talking about classic film photography and not alternative processes, the thing that first attracts most people to the Sustainable Darkroom is the use of chemicals. Unfortunately, at present there is no alternative to colour developer, so we only work with monochrome developers. Typically, commercial monochrome developers make use of Hydroquinone, which is a fossil fuel derivative, combined with Metol or Phenidone - all of which are toxic to yourself and if not properly treated and disposed of, toxic to the ecosystem. Of course there are other commercial developing agents, and generally they are of a toxic nature.

Are some of these toxic chemicals more discussed than others?

Another chemical often discussed is fixative (we skip over stop, as for stop we just use water). Fix is typically made from ammonium thiosulfate or sodium thiosulfate, both of which are relatively low toxicity. The main issue with fixative is that it extracts nano silver from the film, which then collects until the fix becomes saturated. This is a problem if the chemicals aren’t properly disposed of by a waste treatment company - e.g. just poured down a household sink (this is also done by some organisations in our experience!). The silver will enter the waterways and ecosystem and is highly damaging to marine life.

Beyond that, traditional photography is of course reliant on the production of plastics, the use of animal gelatine, the extraction of silver, and other elements embedded within the roll of film which one could argue are detrimental to ecosystems. But by thinking materially, we can start to unpick these legacies and transform photography’s future.

What are the main things analogue photographers can do to reduce their impact on the environment?

I’m sure if you asked Hannah Fletcher (our founder) or Alice Cazenave (our other co-director) we’d all have different answers to this question. Reducing your waste, swapping to low toxic chemistries, shooting only what you need, repurposing and repairing old tech - all of these things are important. But in my view, the first and most essential thing is changing the way we think about photography. Thinking about the past, present, and future of the materials we use and challenging key concepts such as the Kodak moment; letting go of the idea that everything we make has to be permanent and last forever.

What do you hope the future of analogue photography looks like?

There’s no grand vision of storming the steps of Kodak or Ilford and demanding a photographic revolution! I have written before that in an ideal world, there would be a decentralised network of darkrooms operating within Sustainable Darkroom’s principles and techniques, where all aspects of image-making are internalised as much as possible, and waste is reduced and reused to a maximum. But I suppose more broadly, photography being approached from a grassroots perspective and made more accessible, safer, and ecologically regenerative. People can be put off by gatekeeping in the analogue scene, and that is definitely something we try to change whilst including the ecological perspective.

From an environmental point of view should all photographers and filmmakers be abandoning analogue photography and using digital cameras? Do you have any data on the comparative environmental impact between the two?

As it stands, I don’t think there is a comparative study between the two. We avoid being dragged into this debate over which one is better - they both have uses in art and society, and we try not to adopt a stance that tells people they are doing something wrong or should feel guilty. That said, when talking about this topic, I tend to say that with the advent of digital certain harms were reduced - e.g. waste silver in waterways - but the ecological impact of photography wasn’t necessarily reduced overall, as much as displaced into other areas. Some examples are lithium mining for the batteries in digital cameras, the other rare metals for the components, or the use of servers and other data for digital storage and the associated carbon use. At the moment, I can’t really foresee a future where photography can be a totally regenerative practice. It is so tied to our economic and industrial systems of production, which necessitate harm and waste.

Do you see this as an issue with industry or one of changing consumer demand?

To that point, we avoid focusing on personal responsibility. I think this is an idea that arose in neoliberalism as a way to distract from corporate responsibility within ecological issues. We teach people how to develop in plants and so on, but for us it’s important that people understand the economic and social systems that have produced the need for our work in the first place!

The processing, printing and scanning used in the analogue methods in your film must have an environmental impact?

For sure, I definitely still have doubts about my practice and its impact. At one point I stopped taking any photos for a year and just focused on writing as the least impactful thing I could do. That being said, I never thought digital photography would be the solution. Not only because of my own feelings towards digital and the disengagement with the living world it brings, but also because of the other ecological implications of shooting digitally. In terms of my own practice, naturally I find the analogue aesthetic more pleasing, and it’s the most effective way of communicating my own themes of direct engagement and working with the land. Perhaps I should switch to an old digital camera and see how it goes!

When thinking about that side of things, are you ever tempted to simply shoot on a small digital camera or a phone to achieve what I imagine to be a smaller eco-impact? Or how much are you prepared to prioritise the aesthetic of analogue processes?

Photography is so interesting to me because it is so tied to consumerist logic. In a way, it’s like the ultimate art form of our degenerative economic world system, in that it produces millions of images per second around the world. It cannot exist without the production of waste and the exploitation of human and nonhuman bodies, and is completely reliant on endless upgrades and consumer cycles to stay relevant. Ecological writers and philosophers like Donna Haraway or Anna Tsing argue that the best places for ecological renewal are sites of post-industrial ruin, think of your abandoned mining town or a river ruined by toxic waste. I see photography as such a landscape, and so for me wading through an art form, detrimental by nature, is what makes trying to change it more exciting, relevant, and meaningful.

I should also say that we are expanding our research into digital photography. One of our residents, Felix Loftus, built a low-tech, sustainably powered digital camera, and is leading more workshops on this in the future. We hope we can begin to address the world of digital in the future.

What are you working on next?

Personally, I am working with Film London on my next documentary, which is about my home landscape of the North York Moors, exploring parallels between ecological trauma and generational trauma in rural Britain. In terms of the Sustainable Darkroom, we are trying to register as a charity, so we can perhaps get a permanent space in London to teach more workshops and hold more events.

The film highlights what a strong, tight-knit community The Sustainable Darkroom is. How do you plan to grow the community and further spread the knowledge and skills you are gathering?

We share our work in a number of different ways. Firstly, through workshops for students and the public, as well as talks and mentoring sessions. Each month, we run a workshop from our ‘Slow Photography’ series, which tries to combine both theory and practice to create new ways of working. Once a year we also run a workshop week, where we teach everything we know, in collaboration with differing photo organisations. This year it was Intrepid Camera in Bristol. When we succeed in becoming a charity, in-person workshops will hopefully become more formalised and regular, thanks to the funding for a permanent space.

What is the best way for people to learn more?

Beyond teaching we have our publications - three to date - the most recent being ‘re.source’, which is 198 pages of essays, recipes, experiments and more from practitioners all around the world. Our next book is also coming out soon, exclusively covering developers, as this is always a hot topic!

We also run residencies, our previous being the photographic garden residency which features in the film. We are working on getting funding for our next residency, which will focus on the future of photography and photographic materials and systems. The photographic garden residency was very successful, with the research made public online, so we hope this will help us to continue to grow.

How would you like these processes to grow further into mainstream use?

In terms of mainstream use, I think the main thing is to not take too adversarial a stance and encourage further collaborations with industry players and photography organisations, whilst working towards our goal of creating a fully regenerative darkroom that can be shared across the world.

Click here to watch I AM A DARKROOM and follow The Sustainable Darkroom on Instagram.